Have you ever found 222 grams of gold sitting in a bucket? NILU engineer Sam Celentano has.

Earlier this year, engineer Sam Celentano took over responsibility for one of NILU’s instrument laboratories. He started with a thorough tidying and cleaning, during which he found a bucket half full of what looked like small glass tubes filled with heavy pellets. Gold pellets.

Mercury binds to gold

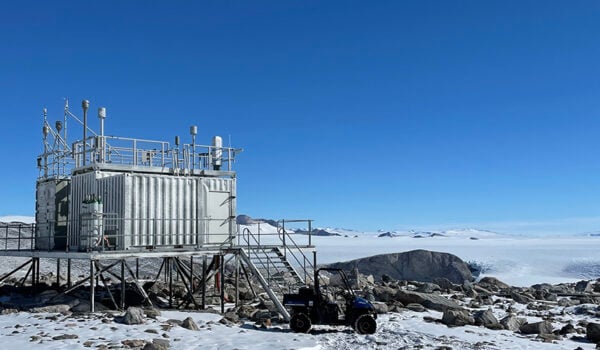

“These pellets originate from our Tekran instruments which we use to measure gaseous mercury in the air. Right now, NILU has four of these instruments running at our observatories Zeppelin on Svalbard, Trollhaugen in Antarctica, Birkenes outside Kristiansand, and Sofienbergparken in Oslo,” says Celentano.

But why is there gold in them?

“We want to measure mercury in the atmosphere, and mercury binds to gold. Ironically, the practice of using mercury to mine for gold has long been one of the biggest sources of mercury pollution,” he says.

In small-scale mining operations, they often mix liquid mercury with gold ore. The mercury binds to the gold, creating an amalgam which is then heated. The toxic mercury evaporates into the air, leaving the pure gold behind. The process also creates a “byproduct”, so-called mine tailings. They also contain mercury, and are released back into the environment, thus polluting the environment near the mines.

Trapping the mercury

The Tekran instrument works more or less as described above. Celentano explains that inside the Tekran are two small quartz tubes. Each contain a tiny capsule of gold pellets pressed together.

The instrument sucks air through the gold pellet-filled tubes, often referred to as traps. They are permeable, so air can easily move through them. The gold will adsorb mercury from the air and trap it in the capsule. Then, the instrument heats the gold traps and flushes them with argon gas enough that the mercury is released to a measurement chamber, which can then give us an averaged concentration.

“We don’t add any mercury to the air during this process. The amount of mercury released from the instrument is the same as was already there to begin with,” Celentano emphasizes.

Costly consumables

Over time, the gold traps get clogged by dust and dirt, so the air can’t pass through. Then the engineers running the instruments will discard the used traps and switch them for new ones.

Celentano has heard that some institutions have tried to clean the traps and reuse them, but it was not very successful. It is a time-consuming process that may be more trouble than it’s worth, other parts of the system may need more frequent service if the traps are constantly removed. In addition, he says they would be unsure of the quality of the monitoring using cleaned traps instead of brand-new ones.

“Over the years, my former colleagues must have replaced hundreds of such gold traps from our Tekran instruments, some of which are more than 20 years old. The traps are ‘consumables,’ but since they weren’t thrown away, my colleagues obviously knew they were valuable. I don’t know if they fully realized, though, because when I found the bucket, it contained more than 150 gold traps,” Celentano says.

222,7 gram gold nugget

Celentano got his colleague Geir Opøien to help him smelt the traps down with an acetylene torch in the workshop.

“Each trap weighs about 1,5 grams, so we ended up with a gold disc weighing 222,7 grams. After visiting several gold buyers in Oslo, I found one that could help both determine how many carats of gold it was and buy it from us.”

Celentano found that few jewelers buying gold are willing to buy lump gold like the one he had. Usually when people sell old gold, it is in the form of jewelry, already hallmarked with carat. Thus, he had to find a shop that had an XRF instrument that could scan the gold lump and determine the purity of it.

“It was 24 carat gold, sitting in a bucket in our instrument lab. Amazing. We sold it for over 150.000 Norwegian kroner,” he says.

“You can see why people go crazy for gold”

NILU’s Monitoring and Instrumentation Technology department, where Celentano works, has a lot of different instruments running at observatories and monitoring stations around the country. He thinks some of them may also contain minute amounts of gold or other precious metals, but not like the Tekran.

He explains that what makes these specific instruments unique is the fact that mercury binds to gold. Thus, it is needed. Instruments don’t contain precious metals just to contain precious metals.

“It was fun to hold the gold lump in my hand, though. You can really see why people go crazy for gold. Almost a fourth of a kilo. It’s probably the most massive thing I’ve ever picked up, gold is almost twice as dense as lead,” he says.

All in all, the money is enough to pay for 8 new gold traps – and according to Sam, it will take around 20 years to collect as many goldtraps again.