Fires in tropical forests affects not only the forest, but also the carbon cycle and air quality. A new study reveals that exactly what burns – and at what temperature – strongly influences the emissions from such fires.

In 2020, scientists registered the largest burnt areas in the Amazon and Cerrado regions in South America since 2010. The annual carbon emissions were also much higher than during the previous decade.

During this intense fire season, biomass – organic material – with an equivalent dried weight of around 372 million tonnes went up in smoke. This led to around 40 million tonnes of carbon monoxide (CO) emissions.

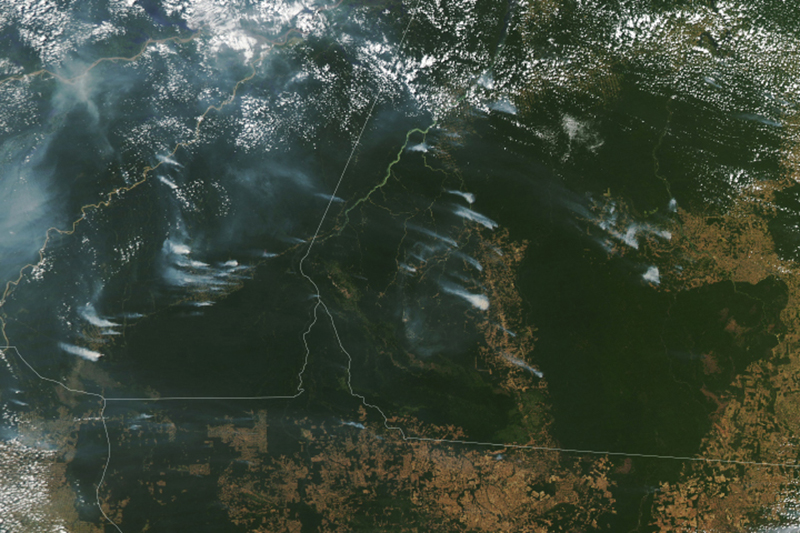

Satellite observations and modelling of the fires

“It is common to use satellites to monitor vegetation fires. They can observe either the heat radiation while the fire is burning, or the burned area afterwards. From either the heat radiation, or the size of the burned area and additional estimates of fuel availability, we know the amount of biomass burned. Then we can also find out how much CO, CO2 and other chemical substances the fires have emitted,” explains senior scientist Dr Johannes Kaiser at NILU.

He is one of the authors behind a recent study published in Nature geosciences, There, a team of scientists has combined various satellite observations and fire models. The aim was to describe the available fuel and combustion conditions more accurately. By doing so, they have managed to reduce the uncertainties in fire emission estimates.

Vegetation fires behave similar to bonfires

In their analysis of the 2020 fire season, the scientists incorporated information on different fuel types, i.e. what kind of biomass was available to burn. They also examined moisture conditions and burning behaviour.

A common fuel type is so-called woody debris, i.e. dead woody plant material. It, and other surface litter covering the forest floor, accounts for around 75 % of the total burned biomass in these areas.

“Vegetation fires in many ways behave like bonfires. For example, fine and dry fuel like dead twigs and small branches burns with flaming. They can ignite coarser fuel, like logs. The logs will afterwards continue to burn smouldering, unless they are piled up. Then they may flame up,” says Kaiser.

He goes on to explain that likewise, savannah fires tend to burn in flaming fronts with relatively little smouldering afterwards.

Fires in the Amazon emit more CO than fires in Cerrado

The scientists compared fire emission and atmospheric models to satellite observations of CO in the atmosphere. By doing so, they demonstrated that burning of woody debris in the tropical Amazon forest often resulted in smouldering fires. These have significantly higher CO emissions than the more combustion efficient flaming fires commonly happening in the savannah region Cerrado. The study thus shows that fire emissions of carbon monoxide in the entire region are dominated by smouldering fires in the Amazon.

“Our results not only highlight the critical role of woody debris in fire emissions. They also show how important it is to merge satellite observations of both the vegetation state and the fires into emission models. Only then can we understand the role of fires in the Earth system and reduce their impact in these vulnerable regions,” concludes Kaiser.