Central Europe is heading towards a hot and dry summer, with increased risk for wildfires. Here in Norway, on the other hand, the risk for rain seems to be greater than the risk of forest fires.

According to Copernicus Climate Change Service, Europe has been warming twice as fast as the global average since the 1980s. It is now the fastest-warming continent on Earth. Last year was the warmest ever, and there is little chance of 2025 slowing the race.

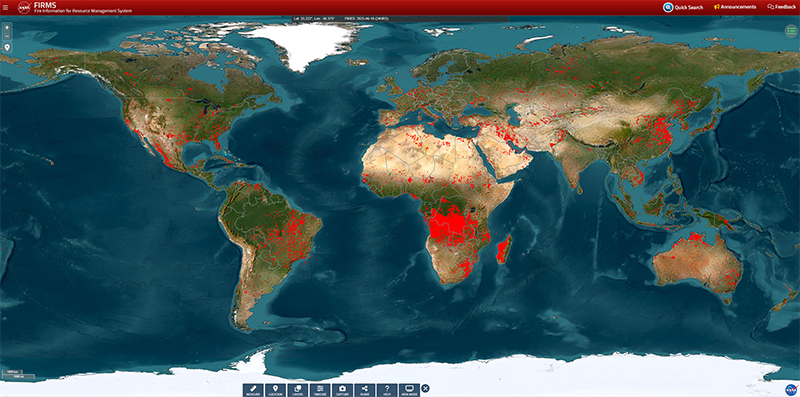

Heatwaves are becoming more frequent and severe, with ever more widespread droughts. With such droughts, the risk of wildfires is rising globally.

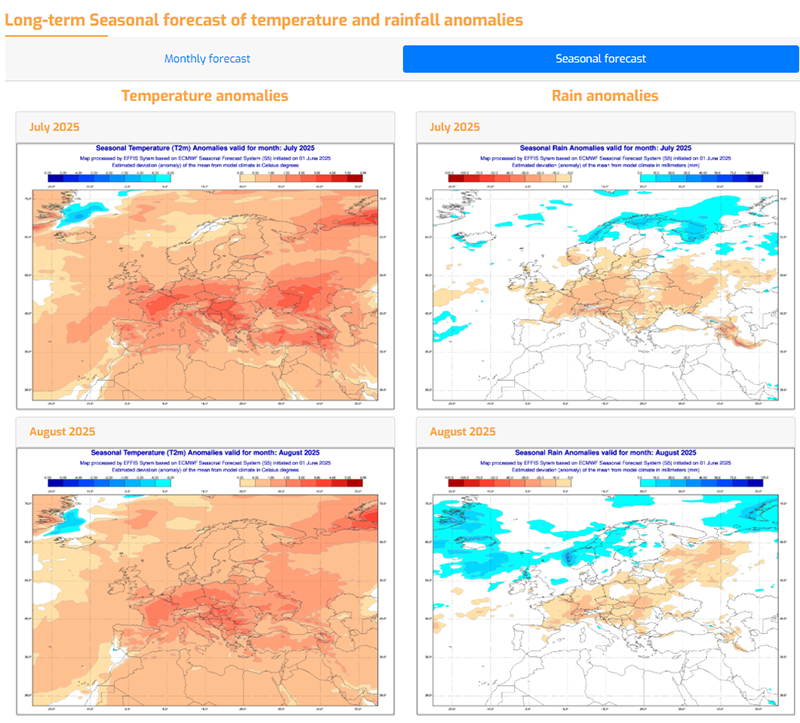

Drought in Central Europe, rain in Norway

“According to the EFFIS Longterm Seasonal Forecast, July and August 2025 are foreseen as hot and dry for central Europe. Hot and dry weather significantly increases wildfire risk by creating favorable conditions for ignition, fire spread, and high intensity. Elevated temperatures and reduced rainfall dry out live and dead vegetation. When they occur at the same time, the desiccation of fine fuels such as grasses, leaves, and twigs on the ground is amplified. This makes them much more susceptible to fire ignition from natural or anthropogenic causes,” says Dr Johannes Kaiser from NILU’s Department of Atmosphere and Climate.

Forecasting can be explained as a process of making predictions based on the study and analysis of past and present data. Later, these forecasts can be compared with what actually has happened and be improved accordingly. Most of us are already familiar with weather forecasting, where weather conditions are predicted on the basis of the most recent meteorological observations.

“Fire danger forecast as seen in EFFIS shows that the fire risk for large forest fires should be low in Norway until end of June. While the forecast shows a warm summer, there are good chances for rain in mid-Norway in July and also in southernmost Norwegian regions in August. This is great for preventing forest fires, but not so positive if you are planning to spend the holiday here,” says Kaiser’s colleague, Dr Nikolaos Evangeliou.

EFFIS is the European Forest Fire Information System. It supports the services in charge of the protection of forests against fires in the EU and neighboring countries. EFFIS also provides the European Commission services and the European Parliament with updated and reliable information on wildfires in Europe.

The so-called Fire Database includes individual and detailed fire records provided by the EFFIS network countries. Currently, data in the database comprises nearly 2 million records provided by 22 countries. Based on this and other information, EFFIS offers several applications for monitoring forest fires and other relevant factors.

“Normal” and “abnormal” wildfires

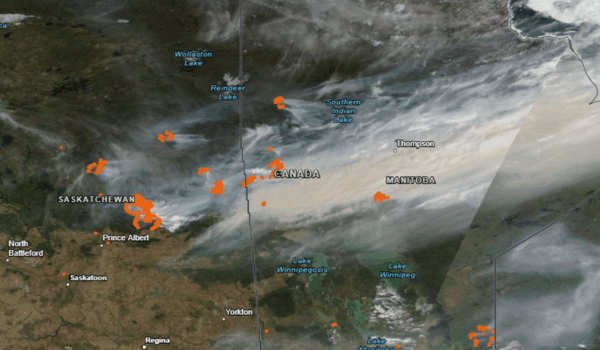

The wildfire season in Canada started in mid-May, and around 200 fires are still raging. Tens of thousands of people have been evacuated from their homes. Most of these fires were ignited by human activity, according to the province of Manitoba’s Wildfire Services website.

“Wildfires are a part of the natural ecosystem, but the fires in Canada are different – and not only because of the human factor. What we see now are fires burning in areas that are normally quite wet, with large, fast-growing forests. Due to drought, these forests are now drier than usual, yielding more available fuel for the fires. In areas which normally are quite dry, you don’t accumulate so much fuel, because you have more frequent – but smaller – fires,” explains Kaiser.

In the past, it was more common for people to gather wood pieces and dry branches from the forest floor and burn them for heat and cooking. By doing so, they removed fuel for wildfires. Another means of keeping wildfires in check is prescribed burning in vulnerable areas.

“In forests as large as in Canada, there is little to no forest management. They don’t thin out the forest, they don’t create firebreaks, there is no clearing of the forest floor. In a lot of European countries, among them my home country Greece, we do such forest management,” says Evangeliou.

The number of extreme wildfires is increasing

Most of Europe will never see fires of a similar size to the Canadian fires. There are simply no forests large enough, agree the two scientists.

“The exception is Siberia, where there have been several fires of the same magnitude during the last ten years,” says Evangeliou.

According to him, Siberia has a similar ecosystem as Canada. It is at the same latitude and also has so-called boreal forests, that is, forests that grow in the High North. They are made up of species that can tolerate cold temperatures, such as spruce and fir. The name “boreal” derives from Boreas, the Greek god of winter, ice and the north wind.

During the summer of 2018, there were more than 50 wildfires in Sweden, many close to the Norwegian border. Altogether, around 216 square kilometers were burning, and fire fighters from several countries worked together to put the fires out.

For Scandinavia, this is quite large. But in comparison, more than 1350 square kilometers burned in Portugal last year, and over 150.000 square kilometers in Canada back in 2023.

“It is a fact that the extreme wildfire risk has risen over the last 20 years,” says Evangeliou. “According to a recent study, where the authors used 21 years of satellite data to identify extreme wildfire events, they have more than doubled in frequency and magnitude between 2003 and 2023. In addition, 2023 had both the hottest global temperature on record and the most extreme wildfire intensities – so far.”